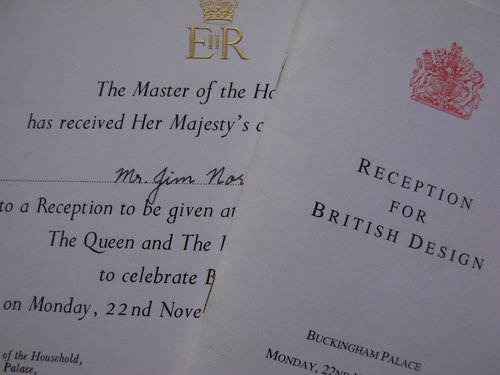

It was not so long ago, although it seems like a lifetime away, the UK was celebrating design and its contribution to the economy and cultural life of the country. Attending a reception at Buckingham Palace exactly six years ago today was evidence enough to me that design had both an influence and a power base.

Now design is on the defensive again, mainly due to the fact that current Government policy has virtually by-passed it from an educational point of view. With science, technology, engineering and mathematics being privileged over the arts and humanities, design finds itself, oddly, on the wrong side of the line. The whole future of design hinges to a large extent on its ability to be a bridge linking the traditionally imagined dichotomy between arts and sciences. There is an intrinsic absurdity in separating the ‘two cultures’, a debate that Snow and Leavis had long ago and is no longer relevant in the current century.

It has been widely reported that the creative industries come only second to finance as the major contributor to the economy, and that in the worlds of architecture, fashion and interaction design UK is one of the global leaders. This not to downgrade the strength of our engineering, bio-science and digital technology sectors, but merely to highlight that design, however you define it, still makes an impact for Britain, working as it does in sectors such as these. A recent survey in the Evening Standard named several designers, arts and media folk as key influencers in London, along with a handful of politicians, one retailer, one banker and no industrialists. The same publication also reported last week that one economist at a leading bank had identified three components that contribute to growth: cash, commodities and creativity. As the Standard’s reporter Anthony Hilton commented, the UK is noticeably short on the first two components, so it’s creativity that counts.

Perhaps some good things will emerge from the Government’s scaling back of support for design education and the design sector. If that does happen, then it would be evidence of creativity in itself – doing more with less. However, a more likely outcome is that design education will be driven into the arms of the corporate world for financial support, sponsorship and resources. No doubt, a ‘real life’ injection might be beneficial, but, equally, objectivity will be compromised. That’s inevitable. Likewise, with the Design Council: its new charitable status may throw up interesting and productive linkages, freeing it from its pact with the Government, but these are uncharted territories and it will need great clarity of purpose if it is to make a successful transition.

In the meantime, the implications for design are not auspicious. Perhaps one day there will be recognition that design can be a central part of our sustainable development as a nation, and one that connects the creative and critical spirits of the ‘arts’ with the objectivity and pragmatism of the ‘sciences’. I look forward to the day when the penny will drop. We may need another royal reception to celebrate it!